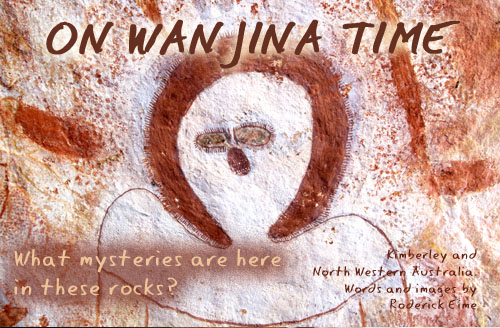

Expedition cruiser, Roderick Eime, comes face-to-face with an ancient hunter born before the ice age.

Blank faced and expressionless, he stood there staring at me. His slender arms adorned with intricate tassels hold a clutch of boomerangs as if inviting me to hunt with him. Literally frozen in time, this ancient gent has held this pose for perhaps 20,000 years.

I sat there staring back with the sort of spine-tingling sensation one experiences when confronted by the alien and inexplicable. He was not alone. Surrounding him were lesser, fainter figures, some dancing, some apparently paying homage, others plain and nude. What does this gathering mean? What is their message?

The Gwion Gwion people of Australia’s Kimberley are long gone, but their art remains in abundance, decorating sheltered rock caves and overhangs, lookouts and frescos throughout an area twice the size of Victoria. Often referred to as ‘Bradshaw Art’, these finely detailed and intricate figures remain a mystery to researchers and academics, fuelling vigorous debate about their origins and meaning.

Some explain them simply as the earliest examples of Australian Aboriginal art, transitioning through several periods over tens of thousands of years. Others, like lifelong researcher Grahame Walsh, believe they belong to a race long since vanished from our shores, even pre-dating current Aboriginal settlement. He draws comparisons with art and cultures as far afield as Papua New Guinea and Africa, but carefully stops short of making the claim as to their origins.

Beyond debate is their obvious contrast to the more modern ‘Wandjina’ art typified by the mouthless, ethereal figures representing the Aboriginal creators and controllers of all earthly things. At many sites the two art forms collide in an uncomfortable jostle that clearly demonstrates the contempt modern Aboriginals held for the Gwion Gwion. Heads of the delicate tasselled men are hammered and defaced in some cases, while elsewhere they are painted over by sprawling murals of the omnipotent Wandjinas.

The pigment used to create the beautiful Gwion Gwion is extremely resilient, so much so that C14 radiocarbon and other scientific dating methods cannot differentiate between it and the rock canvas. An indicator of their age was determined by a fossilised wasp nest built by the insects on top of a Bradshaw figure. It was reckoned to be at least 17,000 years old, placing the art beneath an indeterminate age beyond.

A shrill whistle from Gavin, our guide, interrupted my stupor and signalled time for an urgent return to the tender before the rapidly falling tide stranded us all. I scrambled down the escarpment and across the greedy mud bank, my feet disappearing beyond my knees in my haste to meet the outstretched arms frantically beckoning me aboard. Gavin engaged the outboard and immediately threw up a ‘rooster tail’ of grey-brown muck in an attempt to extricate the struggling craft. Kimberley tides are notoriously treacherous, rising and falling at the rate of over a metre an hour and swinging between ten metre extremes.

Man-handled back aboard, puffing and wheezing from the combined effects of excitement and exertion, Gavin smiles benevolently down on me from the pulpit of the centre-console runabout. “How was that?” he asks plainly as we make our way back to our 1000 tonne mother ship, True North, across the choppy Prince Regent River. “Lost for words?” For once, I was.

Gavin is the chief mate and expedition leader aboard the 36-passenger luxury adventure yacht and has spent most of his working life amongst the billion year old landscape of the Kimberleys. An expert fisherman, boat handler and unrepentant conservationist, Gavin rarely shares his most coveted Bradshaw art sites with guests.

Gavin is the chief mate and expedition leader aboard the 36-passenger luxury adventure yacht and has spent most of his working life amongst the billion year old landscape of the Kimberleys. An expert fisherman, boat handler and unrepentant conservationist, Gavin rarely shares his most coveted Bradshaw art sites with guests.

“If people show a genuine interest in seeing some Braddies,” says Gavin, “we can usually find something on short notice. You and a handful of others are the only ones who’ve ever seen that site.” Yet his extensive catalogue of cave art sites is not recorded anywhere, instead the locations are closely guarded secrets entrusted to a few of the North Star Cruises masters and senior guides alone. “They’re up here,” he replies, pointing a finger purposefully to his temple.

I glance back across the wake of the dinghy trying to spot the high outcrop I had just scaled for my teasing glimpse of the most ancient Australians, but it’s quickly consumed by the enormity of my surroundings. The ship’s Bell jet helicopter races above us, ferrying goggle-eyed passengers back from a swim and frolic in a crystal clear, spring-fed water hole miles inland. Precipitous, golden-hued sandstone cliffs, vast mud banks and mangrove forests typify the landscape that has remained unchanged since before the time of the dinosaurs. Our brief incursion is but a minute speck of time in this geological calendar.

Regardless of your stance on the Bradshaw/Gwion Gwion debate, it’s abundantly clear that my handsome, lithesome hunter, having survived at least two ice ages, will be around long after my entire generation has departed. Perhaps his cryptic code will only be revealed by the next civilisation – if they can even find him again.

Fact File:

North Star Cruises operate the 50 metre, 36-passenger luxury expedition vessel, True North II on six and 12 night itineraries throughout the Kimberley region. Their twenty-plus year experience and intimate knowledge of the largely uncharted river and inlet system sets them apart from other similar operators in Australia’s remote North West.

Prices start from $8995 per person twin share for the six night expedition and $13,995 for twelve nights. Includes all meals, transfers and water-based excursions. Helicopter excursions separate.

For further information contact North Star Cruises on 08 9192 1829 or visit www.northstarcruises.com.au