Originally published in Emirates Portfolio: [See PDF]

The harsh Queensland gemfields attract their fair share of dreamers and drop-outs. Some find their El Dorado, but most luck out. Not Peter Brown.

Some success stories read like a fairy tale. When Peter Brown arrived penniless in the hot, dry and dusty Queensland outback town of Rubyvale in late ‘70s, his decrepit VW combi spluttering and smoking, one could be forgiven for thinking this was some lost hippy bum blowing in from nowhere.

But despite this clumsy beginning, Peter fell entranced with the allure of this tiny village three hours west of Rockhampton, right on the Tropic of Capricorn. Like the neighboring hamlets of Sapphire, Anakie and Emerald, the wealth was hidden in the dirt. Unlike the legendary El Dorado, Rubyvale’s streets were not paved with gold but littered with gems.

The young Peter Brown was transfixed by the tales he heard from the old miners at the bar of the local inn.

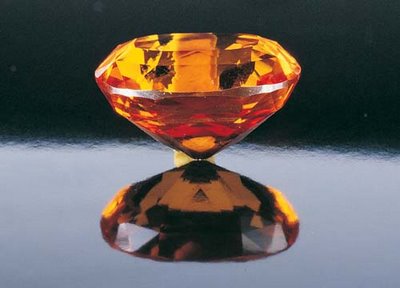

“The yarn that really got me going was one of the local favourites,” recalls Peter, “This 1000-carat rock was found by a 14-year-old in 1935 and was finally cut to become the famous 700 carat ‘Black Star of Queensland’ in 1948 after being used as a doorstop in the family home. Then, no sooner had I arrived in Rubyvale than another kid, Smiley Nelson, kicked up a huge yellow sapphire weighing 2019 carats. This one became another legend, the Centenary Gem and eventually sold for a lot of money. So, the kids were finding these huge gems by accident. I was sure I could find some of my own.”

The rest, as they say, is history. Today, he and wife Eileen operate the multi award-winning Rubyvale Gem Gallery, set up in 1988 in response to demand from both new and repeat buyers.

“We’d outgrown the home-based business and Peter was now pretty good at cutting and setting the stones himself,” recalls Eileen. But she’s being modest. Peter is one of the best known gem cutters in the whole region and his jewel settings are recognised throughout the world, sought after by serious buyers and dealers on every continent.

Inside their restored 1914 miner’s cottage is a showroom more like a big city boutique with shiny display cases full of lustrous gems in their 14 and 18 gold carat settings and gift boxes. Instead of fossicking buckets and gift shop trinkets, Eileen serves visitors Devonshire tea among wild lorikeets in the little garden pavilion and there is even a small cabin for overnighters. Behind the counter, Peter cuts and sets the stones extracted from his private underground mine nearby.

Unlike some of the town’s tourist mines, Peter’s is not for casual visitors. Anybody invited down the shaft must wear a hard hat and clamber down the rickety metal ladder.

Picks and shovels are a thing of the past. Today the hard work is performed by a cast of pneumatic robots, led by an unwieldy-looking mechanised digger. Around the corner a generator throbs away, providing life to this mechanical cave monster. When operating the beast erupts into a fierce crescendo of vibration, devouring great chunks of the grotto wall which tumble onto the floor in a messy heap.

The show continues when a little metal dump truck rolls in and obediently gathers up all the soil and rocks in a noisy, robotic performance. The self-powered unit ambles and stumbles erratically along a makeshift underground railway before disgorging its load into a vertical bucket shaft that transports the material to the surface where an even bigger, uglier monster awaits.

Peter’s surface rig is like something out of a Mad Max movie. This bizarre junkyard sculpture shakes the very ground it stands on as the tonnes of dirt and rocks are violently sorted in a painfully loud drum-rolling process that culminates in a trickle of pebbles issued onto a small conveyor belt. The meagre output is then inspected by hand and the choice stones selected.

Peter and Eileen admit to pressure from overseas markets and lament that their fields were once the most productive sapphire producing areas in the world. “Today large quantities of sapphires are being mined in Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka, Madagascar and China,” explains Eileen with a hint of caution. The earnest look and palpable silence clearly referring to some of the countries which hold little regard for the well-being of their citizens. Like some diamonds from Africa, sapphires, rubies and emeralds can raise money for unscrupulous regimes. Humanitarian considerations aside, Eileen believes the quality of cutting will always distinguish Rubyvale gems from their mass-produced, so-called “native cut” competitors overseas.

“And there’s nothing quite like spending a morning fossicking, finding one or two quality stones and having them cut and set to take home as a special souvenir,” says Eileen, the smile returning to her face.

Mechanical mining ceased in and around Rubyvale over twenty years ago, so the supply of stones is restricted to hand-mining and fossicking. This has the double effect of preserving the environment from over zealous extraction and maintaining the value of the stones.

“Sapphires can occur in any colour and shade imaginable,” continues Eileen, “so except for rubies they are described as ‘green sapphires’, ‘yellow sapphires’, etcetera. We mainly produce the blues, greens, yellows, and parti-colours (mixtures of blue yellow and green), but the odd fancy stones (pink, purple, orange) can also occur very rarely. Peter found a purple recently, but I’m keeping it!”

Hanging on the wall next to the counter are Peter and Eileen’s awards. Their multiple accolades include Specialised Tourism Services, Outstanding Contribution by a Tourism Operator and Significant Tourist Attraction which, when you consider the competition, it’s a pretty substantial endorsement.

“This is an outstanding result” said Alan Chamberlain, General Manager for Capricorn Tourism, the regional tourism authority, “Winning both the Regional and State Tourism award for Retailing and Specialised Services is high praise indeed and taking out both these awards is a well deserved recognition of Rubyvale Gem Gallery’s commitment to continuous improvement and service delivery.”

Featuring in the awards in each of the last three years, earns them Hall of Fame status. Not bad for a bloke who started out with nothing more than a keen sense of both beauty and business – a true gem in the rough.

What is a Sapphire?

Sapphires are precious gemstones along with rubies, emeralds and diamonds. Specifically, they belong to the corundum family, a crystalline form of aluminium oxide. Rubies are actually red sapphires created by chromium impurities, while the softer emeralds are beryllium aluminium silicate with chromium and exclusively green.

Sapphires, while commonly regarded as a blue gem, can actually occur in a wide range of colours depending on the presence of other minerals like iron and titanium. The Central Queensland sapphire fields are probably best known for their yellow and golden stones. These are rare enough to be highly desirable and sell quickly, while other fancy stones like purples and pinks are so rare, that most finders keep them. Depending on size and colour, a cut Q

ueensland sapphire can range between $100 and $2000 per carat.Diamonds are exclusively carbon in composition and their unique crystal (allotrope) is the hardest naturally occurring material but not the most valuable which is, all things being equal, the ruby.

Sapphires are created deep inside the Earth and brought to the surface through violent volcanic action. The Central Queensland Gemfields, situated around the appropriately named towns of Emerald, Rubyvale, Sapphire, Anakie and the Willows Gemfields, are, some believe, still the most productive area in the world for beautiful sapphires. Here the stones can be found on or just below the surface and in ancient alluvial beds as a result of explosive distribution many million years ago. This is ideal for casual fossickers.

The author wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Mr Tony Walsh and the staff at Capricorn Tourism, Rockhampton, in the creation of this story.