As an irrepressibly inquisitive child, I would pore over maps of the great Southern land imagining infinitely white vistas, ice-encrusted shorelines and flocks of bizarre creatures engaged in all manner of noisy rituals.

Then

this fledgling student of geography, in the grip of idleness, would often

identify the most isolated and unlikely points on the globe, vowing one

day to venture to these invariably far-flung and often wholly inhospitable

lands. Antarctica's treacherous, spiny tendril was one such irresistible

location.

Then

this fledgling student of geography, in the grip of idleness, would often

identify the most isolated and unlikely points on the globe, vowing one

day to venture to these invariably far-flung and often wholly inhospitable

lands. Antarctica's treacherous, spiny tendril was one such irresistible

location.

Like the bristly tail of some giant, prehistoric sea creature, the Antarctic Peninsula thrusts out past the Antarctic Circle, lunging vainly toward its sibling, the Andes, across the infamous Drake Passage. As far as the Antarctic is concerned, the peninsula is the most densely populated location on the continent, sprinkled with vast research bases and minute outposts alike. At the height of the summer season, the human population numbers over 3,000 - not counting tourists. That figure shrinks to less than 1,000 during the intensely chilly winter.

Fast-forward thirty years and that misty dream becomes reality. I'm standing on the bow of a modern ice vessel watching hefty chunks of disintegrating pack ice thud against the hull as we pick our way gingerly through a narrow channel. Lonely groups of Adélie Penguins watch curiously as we inch past, while in the distance, a lone Leopard Seal dives for cover under the flow.

Having

already traversed the waters from The Falkland Islands to South

Georgia and penetrated the snoozing caldera of Deception

Island, the Akedemik Sergey Vavilov and its seasoned crew prepare

to make the perilous entry into the ever-diminishing confines of the frozen

waterways amongst the Palmer Archipelago.

During the pre-dawn,

Vavilov enters the relatively broad expanse of the Gerlache Strait and

well before the first smell of morning coffee wafts up from the galley,

we're perched around the bow, goggle eyed, as the snow-splattered peaks

embracing the Lemaire Channel loom above us. This is the sort of vision

that lasts to the grave - a manic chequerboard of ice chunks, too small

to be called 'bergs' are arrayed out before us. Now at a virtual crawl,

the Vavilov gently nudges them aside, the ice-strengthened steel bow ushering

them delicately around the hull amidst muffled, squeaking protests.

After a suitably reinforcing breakfast we reached our southernmost point, Petermann Island, where a very basic survival hut erected by the Argentines in 1955 provides essential food, shelter and magazines for marooned explorers - handy to know if I miss the last zodiac home. A cross erected nearby bears witness to those who didn't make it. Apart from the curious hut, the little outpost plays host to the southernmost flock of breeding Gentoo Penguins while Sheathbills, Shags and the ever-opportunistic Skuas patrol nearby.

The

return journey was interrupted with some leisurely zodiac cruising amongst

the grounded icebergs off Pleneau Island. Seasoned by a stiff, sleety

breeze, the scene is like a frozen graveyard - these doomed bergs aren't

going anywhere. Arranged in totally random assortments, these guys are

gathered here from all around the peninsula, their normal migration halted

permanently by the shallow harbour. No two even vaguely alike, these forlorn

sculpted slabs still exhibit their marvellous range of intense blue dictated

by varying oxygen density. Our passage is often slowed by a thickening,

smoky pane of ice forming before us and we are forced to bash our way

through with oars as the lightweight zodiac displays its total lack of

ice-breaking capability. Heads suddenly swivel and twitch as a timid female

Leopard seal and pup suddenly appears, and just as mysteriously disappears,

amongst the frosted icescape - a rare sight even for experienced expeditioners.

The

return journey was interrupted with some leisurely zodiac cruising amongst

the grounded icebergs off Pleneau Island. Seasoned by a stiff, sleety

breeze, the scene is like a frozen graveyard - these doomed bergs aren't

going anywhere. Arranged in totally random assortments, these guys are

gathered here from all around the peninsula, their normal migration halted

permanently by the shallow harbour. No two even vaguely alike, these forlorn

sculpted slabs still exhibit their marvellous range of intense blue dictated

by varying oxygen density. Our passage is often slowed by a thickening,

smoky pane of ice forming before us and we are forced to bash our way

through with oars as the lightweight zodiac displays its total lack of

ice-breaking capability. Heads suddenly swivel and twitch as a timid female

Leopard seal and pup suddenly appears, and just as mysteriously disappears,

amongst the frosted icescape - a rare sight even for experienced expeditioners.

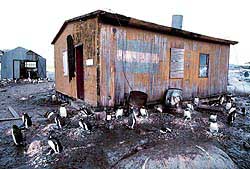

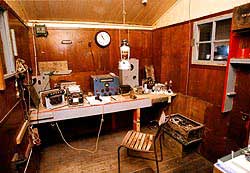

Next

port of call is the recently refurbished, Port

Lockroy on tiny Goudier Island. Abandoned by the British Antarctic

Survey in 1962, the cute hut is chock full of artefacts from the mid 20th

century's Antarctic expeditions and is now a heritage listed site. A radio

room, a galley and a working post office where you can send a genuine

Antarctic postcard and get your passport stamped. More like monks than

caretakers, Dave and Nigel cheerfully answer questions while dispensing

stamps and souvenirs at the most visited place on the peninsula.

Next

port of call is the recently refurbished, Port

Lockroy on tiny Goudier Island. Abandoned by the British Antarctic

Survey in 1962, the cute hut is chock full of artefacts from the mid 20th

century's Antarctic expeditions and is now a heritage listed site. A radio

room, a galley and a working post office where you can send a genuine

Antarctic postcard and get your passport stamped. More like monks than

caretakers, Dave and Nigel cheerfully answer questions while dispensing

stamps and souvenirs at the most visited place on the peninsula.

Our

final and most significant landfall is the Chilean mainland base of Gonzales

Videla at Waterboat

Point, where we set foot on Antarctica proper. I suspect our expedition

leader, Julio, a burly Chilean himself, was trying to bolster his country's

economy when I saw the vast array of souvenirs laid out for our inspection.

The table quickly cleared and the contingent hastily withdrew to quantify

their spoils. The location is so named because two typically foolhardy

Englishmen wintered there in 1921-22 in an abandoned Whaler's boat. The

boat itself, oozing history, was burnt by the Chileans as junk. The guano-coated

base is completely overrun by incontinent Gentoo Penguins, all fiercely

protected by the dozen or so military personnel who are quick to interdict

if wandering visitors stray too close.

Our

final and most significant landfall is the Chilean mainland base of Gonzales

Videla at Waterboat

Point, where we set foot on Antarctica proper. I suspect our expedition

leader, Julio, a burly Chilean himself, was trying to bolster his country's

economy when I saw the vast array of souvenirs laid out for our inspection.

The table quickly cleared and the contingent hastily withdrew to quantify

their spoils. The location is so named because two typically foolhardy

Englishmen wintered there in 1921-22 in an abandoned Whaler's boat. The

boat itself, oozing history, was burnt by the Chileans as junk. The guano-coated

base is completely overrun by incontinent Gentoo Penguins, all fiercely

protected by the dozen or so military personnel who are quick to interdict

if wandering visitors stray too close.

We

salute the Chilean flag that flies above the ashes of the original water

boat, knowing that this will be our last view of the Antarctic mainland.

The aptly named Paradise Bay is the epitome of classic Antarctic Peninsula

scenery. Deceptively tranquil waterways dotted with ice cakes and framed

by snow-dusted cliffs, completely silent except for the occasional screech

of a wheeling seabird.

We

salute the Chilean flag that flies above the ashes of the original water

boat, knowing that this will be our last view of the Antarctic mainland.

The aptly named Paradise Bay is the epitome of classic Antarctic Peninsula

scenery. Deceptively tranquil waterways dotted with ice cakes and framed

by snow-dusted cliffs, completely silent except for the occasional screech

of a wheeling seabird.

I believe we all posses

a photographic memory, and when I close my eyes and recall these evocative

vistas in all their glory, I'm grateful for this small power of the mind.

Occasionally I blow the dust off my weighty old atlas and childishly smile

that certain knowing smile as my eyes pass along what were once simply

maps but are now living, full colour diaries of adventure.

Words and Pictures by Roderick Eime

Where is the Antarctic

Peninsula? - See

The Map

How to Get There - Adventure

Associates

Related Links: BAS

: Scott Polar Research

Institute

|

|

|